The Mastabas of Qar and Idu G 7101 and 7102 - Digitally Revised and Enhanced Edition

Part II - Idu G 7102

Section 2.1 - Facade - Preparing the Photo Background

Written by Owen Murray, photographer at the Epigraphic Survey of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago

In order for the digital redrawing to take place, an orthorectified photo background was needed. It should be noted that this project took place during the second year of the SARS Covid-19 pandemic, and that the proper permissions for field photography including survey measurements and proper lighting were not an option. Under normal circumstances, a local coordinate survey and/or laser scan of each Mastaba would have been completed, then paired with high resolution digital photography using studio lighting for photogrammetry. The result of this workflow in terms of 2D epigraphic documentation purposes would be an orthorectified photo background suitable for drawing at a scale of 1-4@1200ppi.

As this was not an option, the background for this digital redrawing was created photogrammetrically using three different datasets: a 2019 series of photos taken for a virtual tour of the Qar & Idu Mastabas by Luke Hollis; a 2021 series of photos taken to provide the level of detail required for drawing the facade at a scale of 1-4@300ppi by Marleen De Meyer; as well as a set of five 6.5”x8.5” glass plate negatives taken by Mohammedani Ibrahim between 1925-1940, and subsequently scanned by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

On their own, none of the datasets had enough information to accurately scale and measure them; the virtual tour and detailed data sets lacked any calibration source, while the archival set, as one might expect, contained only scale bars placed in individual photos. Though by no means ideal, this issue was overcome by combining the datasets together; the virtual tour photos allowed the accurate placement of both archival and detailed datasets, and scale was set using a 50cm section of a 1m scale bar placed in Ibrahim’s 1925 overview of the tomb facade during excavation (B5575_NS). This was then checked and measured in the rectified orthomosaic after building the model. The error margins are within 5mm.

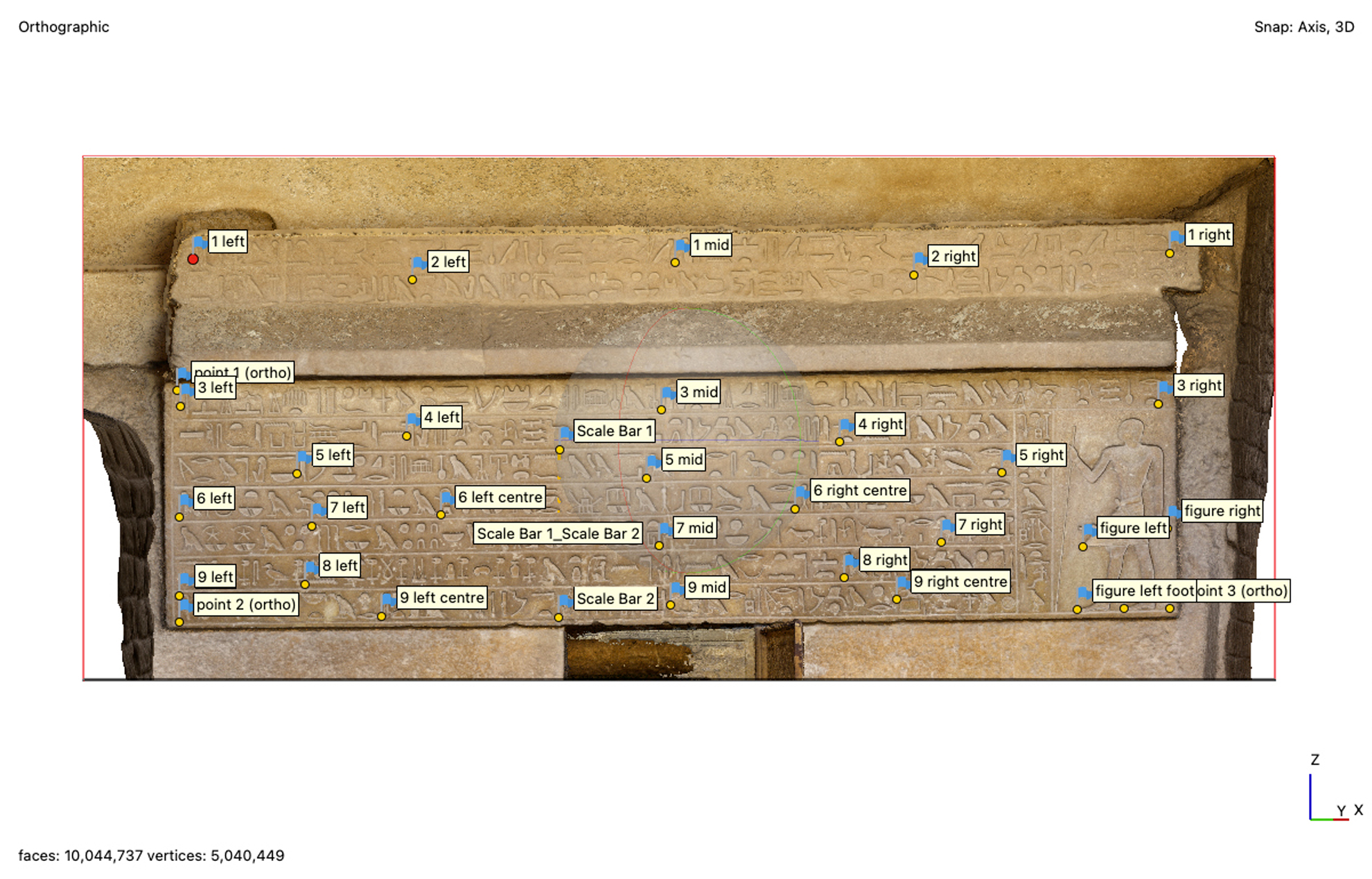

Both the virtual tour and detailed datasets contained enough overlap between individual shots to allow their photogrammetric assembly without the use of targets. However, in order to more accurately align these two sets, and integrate Ibrahim’s archival photos, a series of 29 points were hand-picked and identified in all three datasets. Four corner positions were input first, after which a range of points distributed equitably across the length and width of the architrave were chosen.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the 29 points used in aligning the three different datasets.

In most cases sharp corner areas on carved glyphs were used for point placement as their identification across the range and quality of photographs in each of the three datasets was most easily determined. For further reading and a detailed tutorial on this process please see Modelling the Past: Creating 3D Models from Archival Imagery.

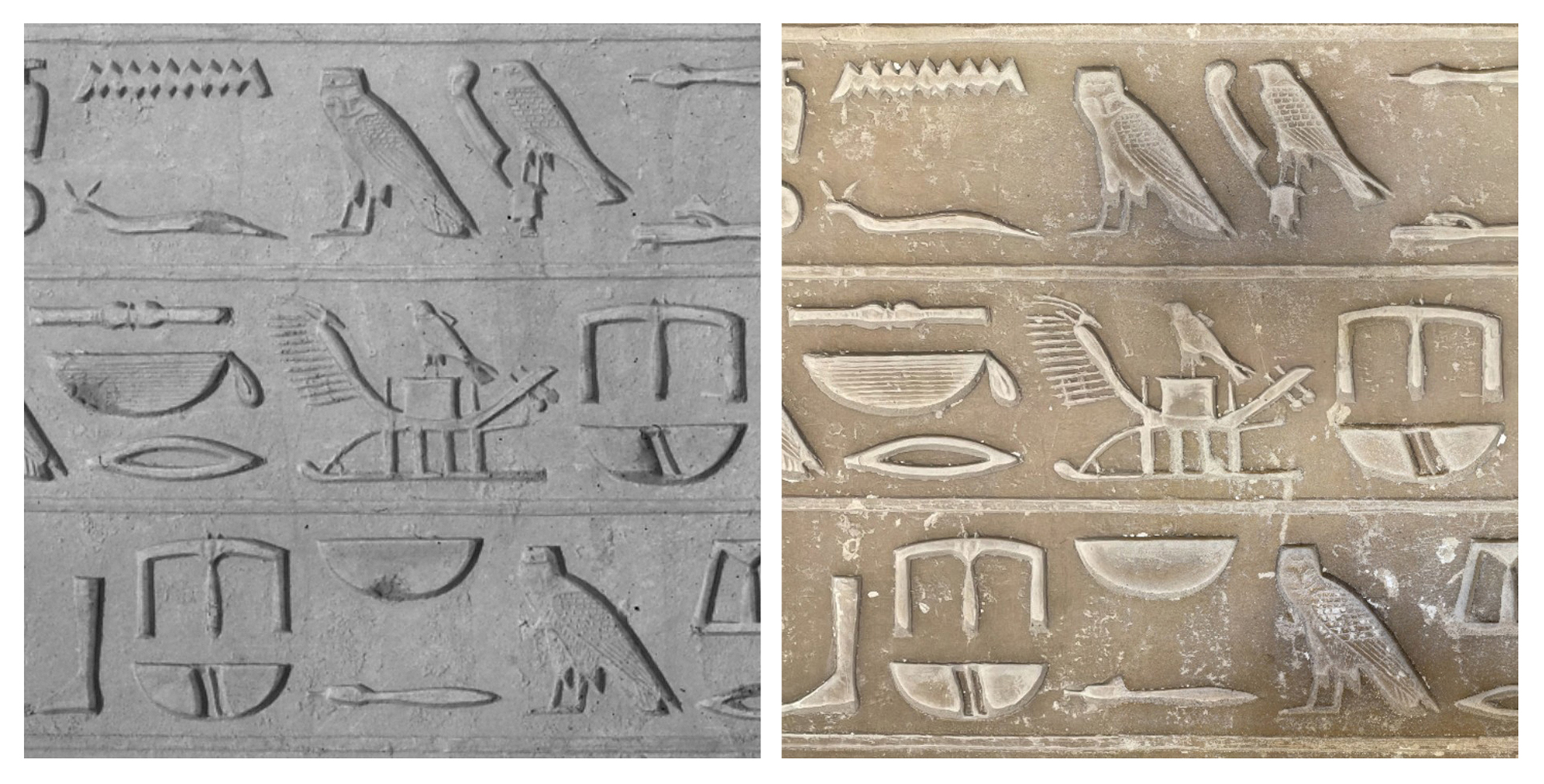

With all datasets effectively aligned and scale set, a combined model was built and a series of 5 orthomosaics were produced: 1925 mid-excavation with scale bar (Jan/10/1925), 1925 post-excavation (Mar/21/1925), 1940 publication photography with studio lighting (July/21/1040), 2019 virtual tour and 2021 detail photography. These orthomosaics were exported at 0.845mm/px ratio for a photo background at a scale of 1-4@300ppi. Of the five, only the 1940 publication with studio lighting and 2021 detail photography provided suitable results for the scale and resolution specified (fig 2). De Meyer's 2021 detail photography orthomosaic was selected by Krisztián Vértes and used for digital redrawing.

Figure 2. Screenshot detail (@100%) of the same section between the 1940 publication photography with studio lighting (on left) and 2021 detail photography (on right).

Although field work was not possible, and as such the optimum workflow for both photography and drawing documentation unattainable, this manner of working does demonstrate that archival materials can not only be integrated into current cultural heritage best documentation practices but relied upon to generate results for their epigraphic interpretation.

0 comment(s)

Leave a comment(We'll keep your email address private)