Digital Epigraphy (Second Edition)

Chapter 1 - The Epigraphic Survey

Chapter 1 - The Epigraphic Survey

Written by W. R. Johnson

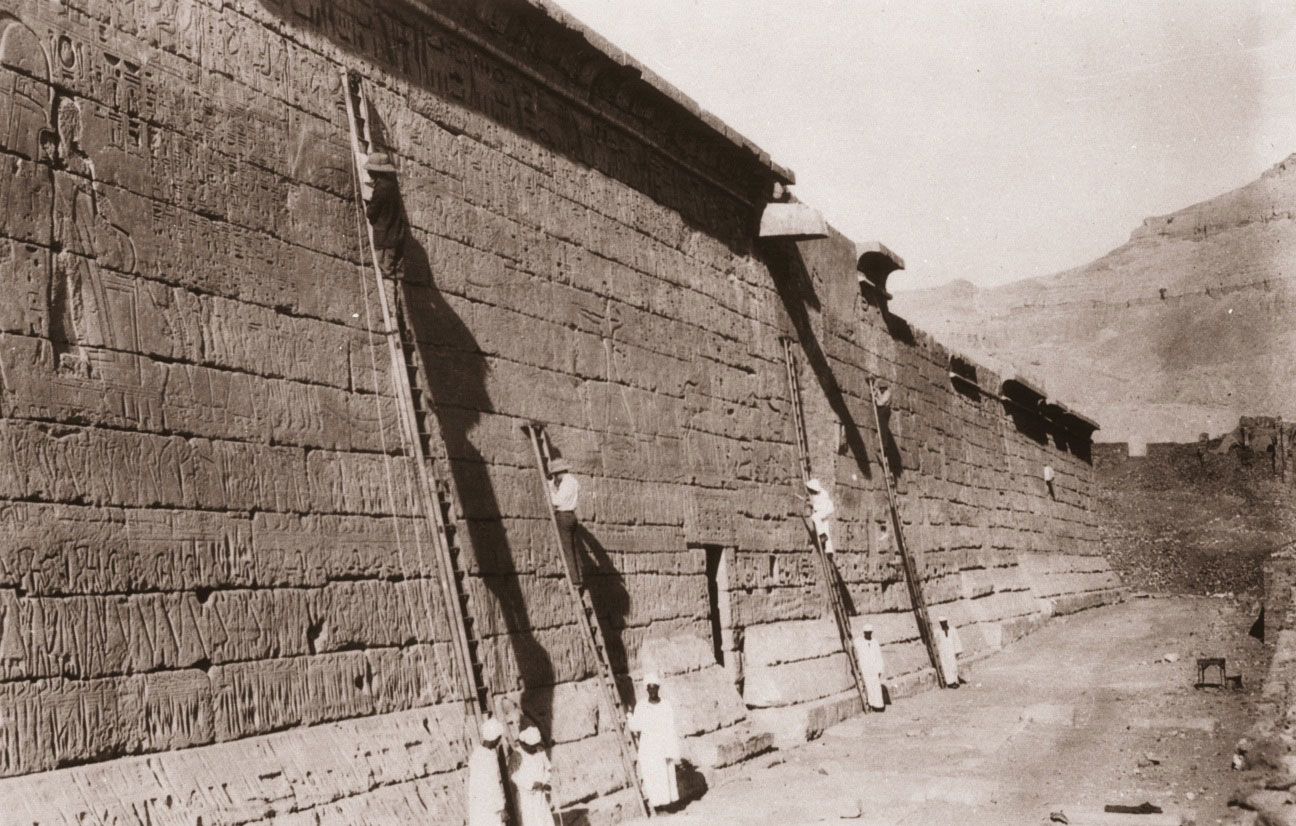

Epigraphic Survey staff working on the wall at Medinet Habu in 1928

In 1923 Oriental Institute founder James Henry Breasted conceived the idea of a permanent field headquarters of the Oriental Institute, based in Luxor, for a long-term epigraphic and architectural survey of all the ancient temples of the Nile Valley. This project would start with the extensive monuments of ancient Luxor itself, beginning with the great mortuary temple complex of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu in western Thebes. Breasted sent a draft of his vision to Dr. Harold H. Nelson, head of the Department of History at the American University of Beirut and convinced him to be the first director of what came to be known as the Epigraphic Survey of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago.

Establishing the Survey

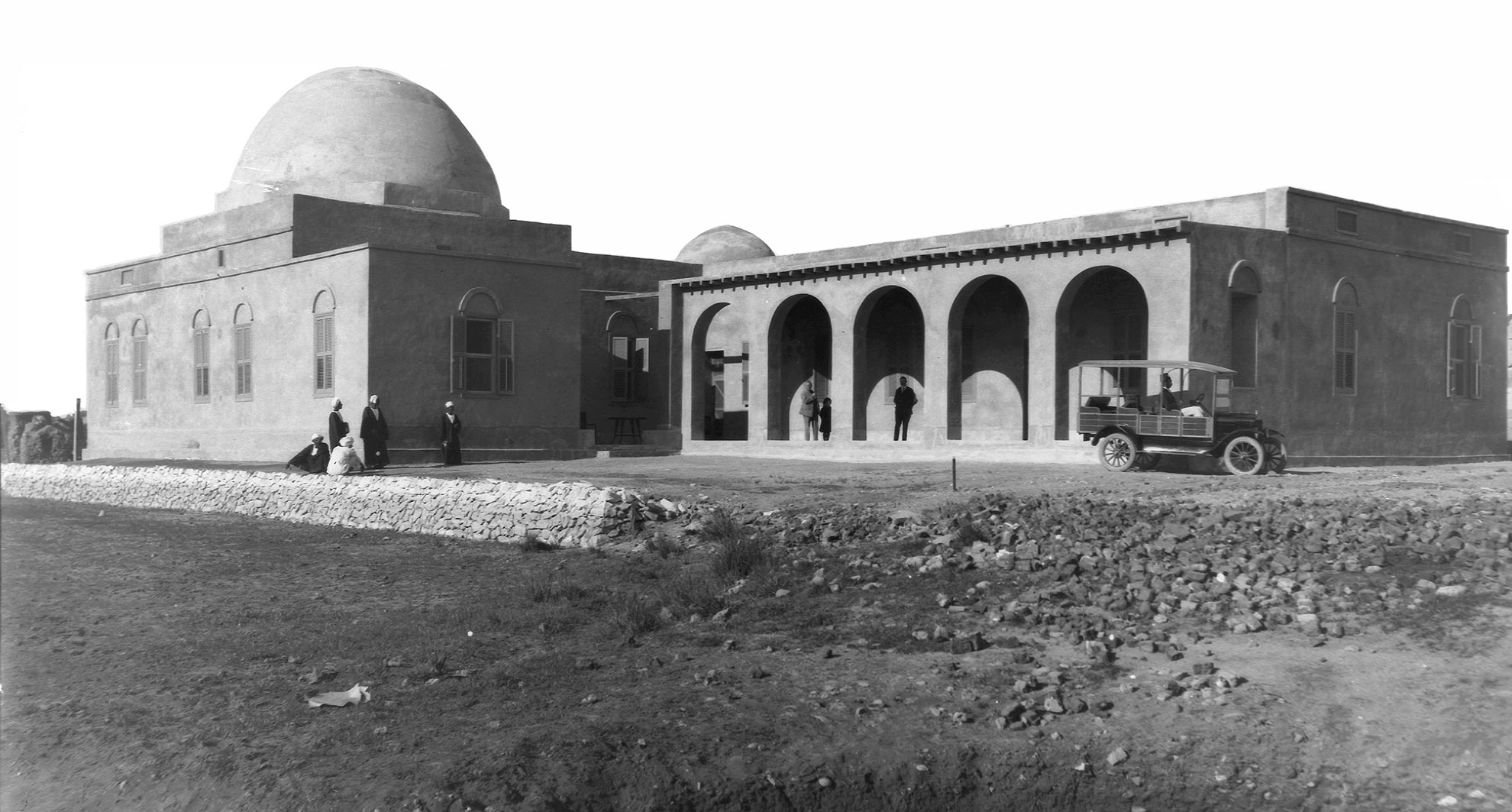

Chicago House as seen from the air in 1933

Breasted himself designed the first expedition field house on the west bank to the north of Medinet Habu, and the construction of the first “Chicago House” was supervised by A. R. Callender, who had been an assistant to Howard Carter. The field house was completed by the summer of 1924, and in October 1924 the expedition members moved in. On November 17th work began at the great mortuary temple of Ramesses III; the Epigraphic Survey was launched and continues to this day. In 1926 the Architectural Survey was also established at Chicago House under the directorship of Professor Uvo Hölscher of Hannover, Germany. In addition to documenting and analyzing the considerable architectural remains at Medinet Habu, Hölscher also directed excavations at the site (already started in the nineteenth century by John Beasley Greene, Georges Daressy, etc.), at the Ramesseum, and the mortuary temple complex of Ay and Horemheb immediately to the north of Medinet Habu. His drawings, plans, and reconstructions of the Medinet Habu complex and environs are among the best ever done of any site in Egypt.

In 1930, the original mudbrick and wood Chicago House facility, despite numerous additions, was clearly insufficient for the needs of the growing expedition. Thanks to a generous gift from John D. Rockefeller, Jr., three and a half acres of land for the present facility were acquired on the east bank of Luxor in 1929, north of Luxor proper and just south of Karnak, on the Nile. Two young University of Pennsylvania architects, L. LeGrande Hunter and L. C. Woolman, drew up plans in close consultation with Breasted, and construction of the present-day Chicago House began in 1930. The complex, consisting of a main residence wing, a large library and office wing, art studios, photography studio with three darkrooms, and back garage and support area, was constructed of permanent materials (stone, baked brick, and reinforced concrete) and was completed in 1931. The professional staff took up residence in 1932. The old facility on the west bank was kept as a rest house for the Medinet Habu epigraphic staff and archaeologists but was later demolished in 1940. (Architectural elements from the original house, as well as the land, were sold to Sheikh Ali Abdul Rasool, who used them to construct the Marsam Hotel and rest house on the original site, still in operation today.)

Old Chicago House on the West Bank in 1924

Breasted’s dream was to record with precision all the monuments of Egypt, starting in the south. In 1930–1931 that vision was extended northward to the site of the ancient political and administrative capital of Egypt, great Memphis, established by Menes/Narmer at the beginning of the First Dynasty. Here was constructed, again with the support of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., an expedition field house that would house a second, northern epigraphic expedition, whose purpose was to record the ancient Old Kingdom monuments of Saqqara.

Epigraphic Recording

Margaret De Jong drawing on photo enlargement at Medinet Habu

The fact that anything from Egypt’s remote antiquity survives to the present day is nothing short of miraculous. Yet over the thousands of years since the eclipse of pharaonic civilization, Egypt’s dry climate and low population allowed the preservation of much of the ancient landscape, particularly in the south, where the majority of the best-preserved temple sites are to be found. Temples, mortuary complexes, and even cities, an astonishing array of cultural heritage sites, with literally miles of inscribed walls, offer us today a wealth of information about these deep roots of Western civilization. Unfortunately, the conditions that allowed their preservation are now rapidly changing as weather patterns shift and Egypt’s population grows. Even in Breasted’s day he could see beautifully inscribed wall surfaces slowly fading and vanishing in front of his eyes, as wind and rain and the depredations of man scoured the fragile, ancient stone. Higher air humidity, growing cities, and agricultural expansion are now causing that decay to accelerate alarmingly. In recent years the Epigraphic Survey has added conservation and restoration to its programs, in addition to its core documentation work, in an effort to help keep up with Egypt’s rapidly changing environment.

The Recording Process

The point of epigraphic recording, and the primary task of the Epigraphic Survey even today, is to create precise facsimile copies of the carved and painted wall surfaces of Egypt’s ancient temples and tombs in order to preserve for all time the information found on them as part of the scientific record. Breasted believed that this documentation should be so precise it could stand in for the original. The documentation program of the Epigraphic Survey was designed accordingly, and today the drawings and photographs produced by Chicago House are so exact that they are even used by conservators in the physical consolidation and reconstruction of those walls as a fixed reference to their condition at the time of recording.

Large Format Photography

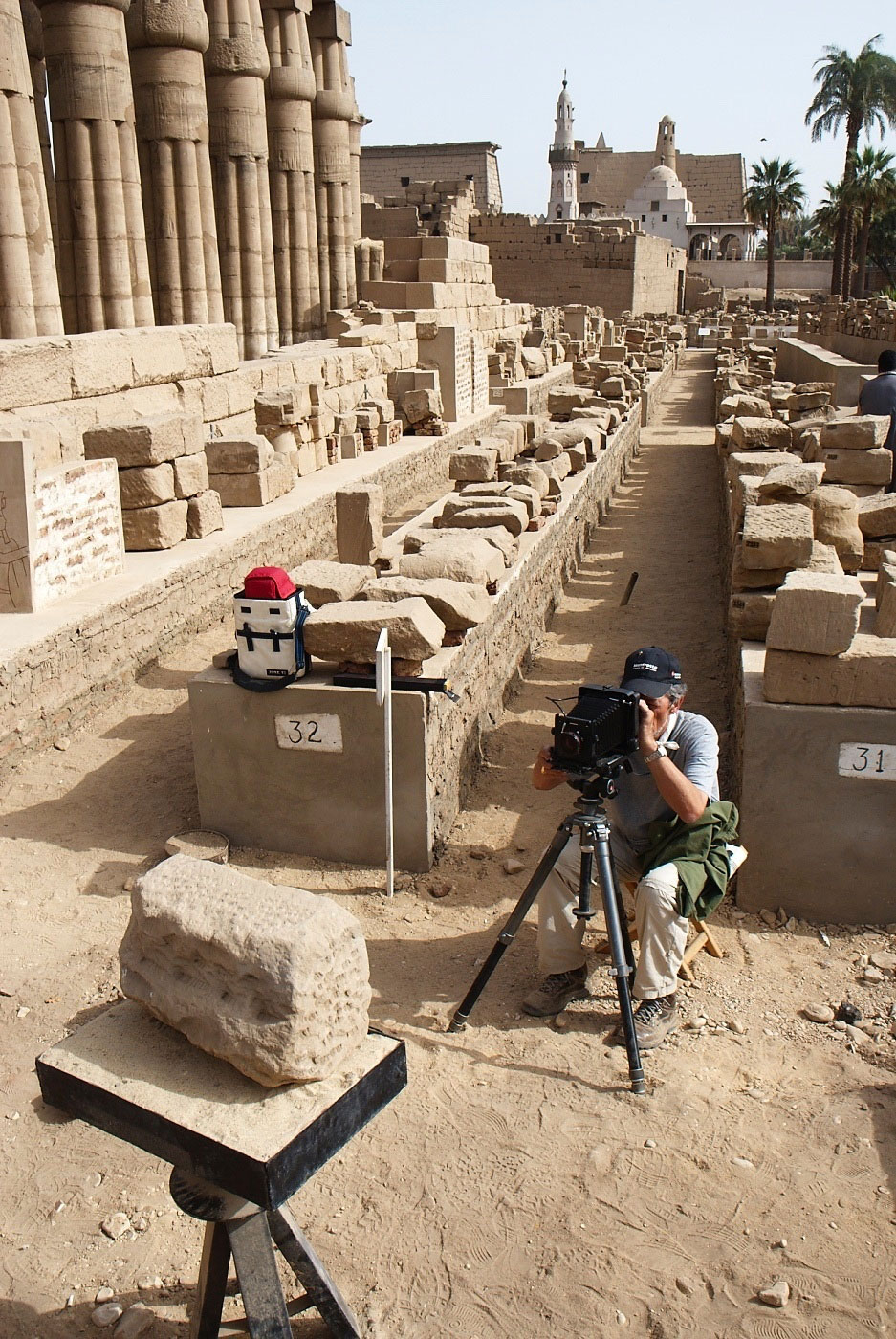

Yarko Kobylecky photographing Luxor Temple blocks

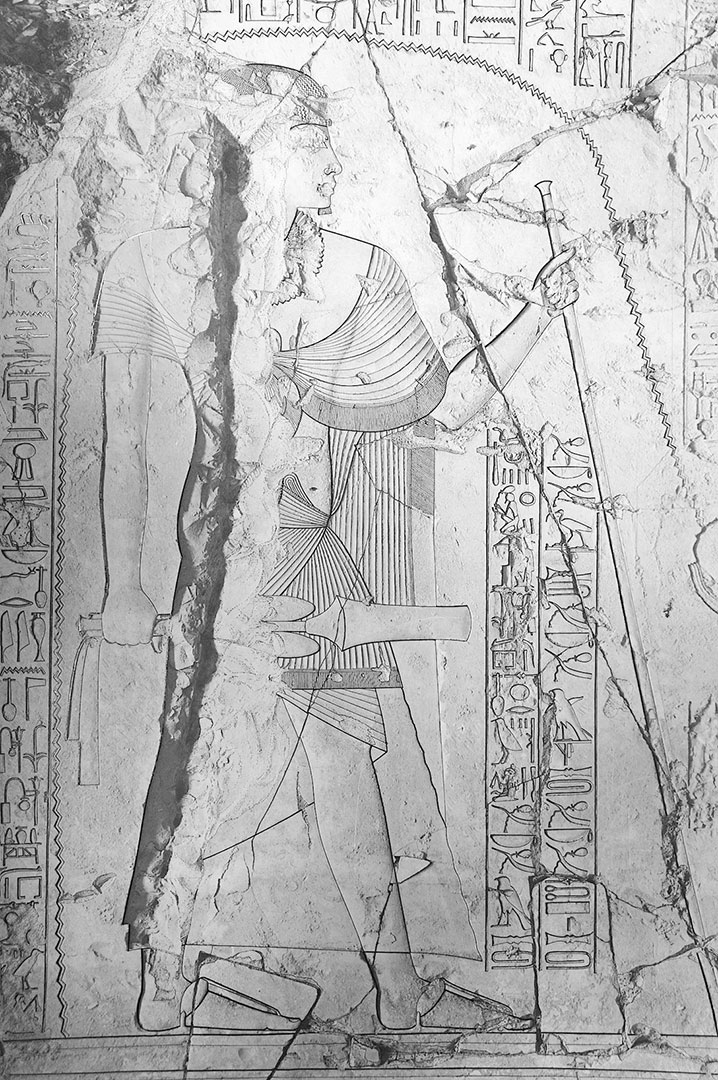

Archival large-format black-and-white (and color) film photography (8 x 10, 5 x 7, and 4 x 5 inches) was, and still is, the first step in the recording program of the Epigraphic Survey. In recent years this has been supplemented with digital color photography, and in all cases, large-format negatives are now also digitally scanned. Hard copy contact prints are made directly from the black-and-white negatives, and these form the core of the Chicago House Photographic Archives, which presently houses over 20,000 negatives and 21,000 prints. Our digital image archive is considerably larger and is growing rapidly. Intact carved wall surfaces and well-preserved painted plaster walls can be recorded quite well with photography alone.

Many of the walls and inscribed columns in the mortuary temple of Ramesses III, for instance, do not require drawings, and so they are published in clear, crisp black-and-white photographs that show most, if not all, of the inscribed details. More recent digital photography can now capture and reproduce color and painted details on wall surfaces in a way that is quite extraordinary. Three-dimensional imaging can capture a tremendous amount of information as well.

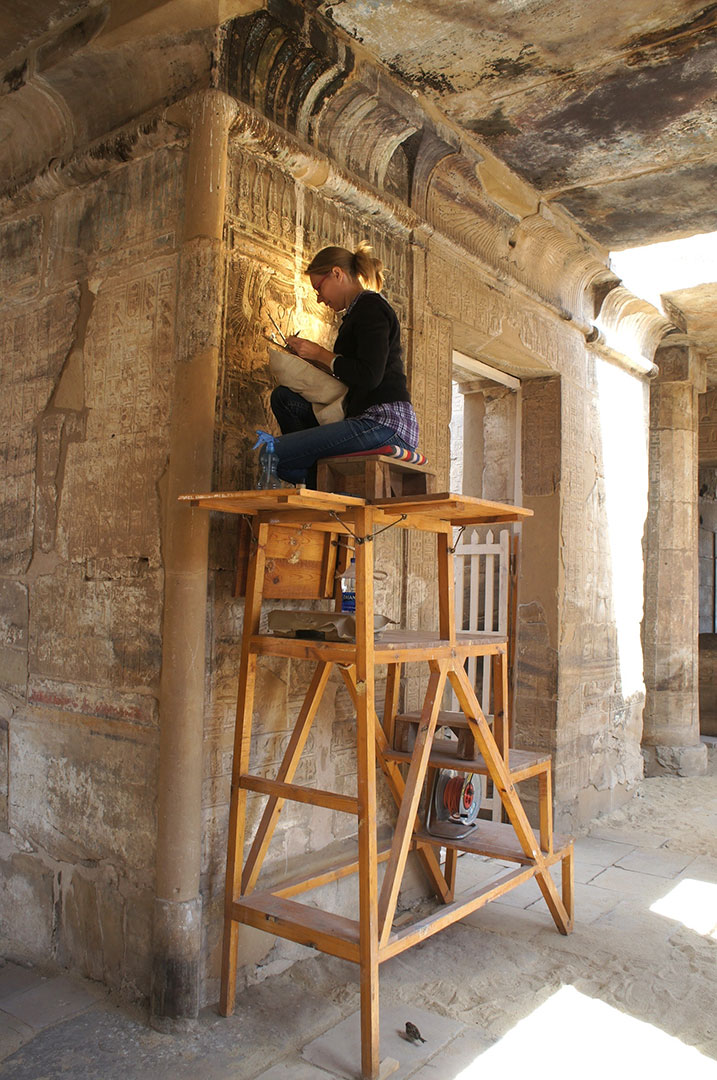

Keli Alberts penciling at Medinet Habu

The Photographic Method

Although an avid photographer himself, Breasted quickly learned through experience that unless an ancient inscribed wall surface is in a pristine state, photography alone often cannot capture all the details that are preserved on it. In the case of a wall surface that is damaged or has been modified through recarving, many details that are visible to the naked eye are often invisible to the camera lens. In cases like these, to supplement and clarify the photographic record, precise line drawings are produced at Chicago House that clearly present the carved details and combine the talents of the photographer, artist, and Egyptologist.

Photography is still the first step. First, the wall surface is carefully photographed with a large-format camera whose lens is positioned exactly parallel to the wall to eliminate distortion. A series of photographic film negatives are taken along the length of the wall, each the same distance from the wall, taking care to make sure that the edges of each overlap slightly for joining of scenes later. From these negatives, when necessary, photographic enlargements up to 20 x 24 inches are produced, printed on a special matte-surface paper with an emulsion coating that can take pencil and ink lines.

All hard-copy negatives and duplicates are archived at Chicago House and the Oriental Institute, and all negatives are scanned at high resolution for digital archiving in both locations as well.

Penciling on Enlargement - An artist takes the enlarged photographic print mounted on a drawing board to the wall itself and pencils all the carved details that are visible on the wall surface directly onto the photograph, adding those that are not visible or clear on the photograph. This non-invasive system, where no tracing paper or plastic is ever pressed against the wall, is particularly well suited to fragile, decayed wall surfaces that should not be touched.

Inking- Back at the Chicago House studio, or at home during the summer, the penciled lines are carefully inked by the artist with a series of thin and thick black lines to show the three dimensions of the relief (thin where the hypothetical sun, always from the upper left, strikes the reliefs, and a thicker line where a shadow is cast).

Damage that interrupts the carving is rendered with very thin, broken lines that imitate the nature of the break. With care, a skilled artist can indicate with the inked line alone whether the stone is limestone or sandstone, and even differentiate between natural damage and deliberate defacement.

Inked drawing enlargement from TT 107 Drawing by Osgood

Bleaching and Blueprinting- Traditionally, when the India inking has been completed, the entire inked photograph is immersed in an iodine bath that dissolves the photographic image containing all the “background noise” that obscures the carved information, leaving just the ink drawing of the carved details and any damage that interrupts the carved line showing very clearly on the white photographic paper. In the case of digital inking, the photographic “layer” is simply turned off and the grayscale background disappears, leaving just the inked lines against a white background. The drawing is then blueprinted, scanned, or in the case of the digital drawing, printed out.

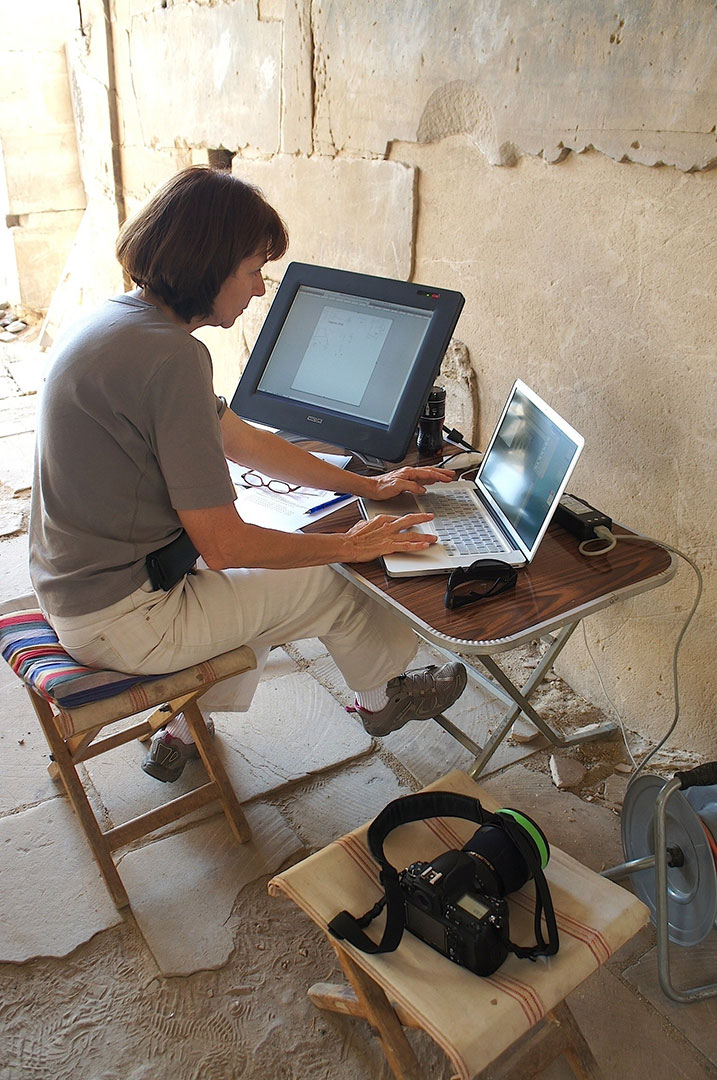

Collation Process- The blueprint or print is cut into sections, and each is mounted on a sheet of stiff white paper. These “collation sheets” are taken back to the wall where the inked details are thoroughly examined by two Egyptologist epigraphers, one after the other (the “first epigrapher” and the “second epigrapher”). The collation step of the process is a crucial component in all epigraphic recording and allows several sets of additional eyes to extract from the carved wall surface additional information that otherwise might be missed. The epigraphers pencil corrections and refinements onto the blueprint itself with explanations and instructions to the artist written in the margins. When the epigraphers have met and consolidated their corrections, the collation sheets are then returned to the artist, who in turn takes them back to the wall and carefully checks each correction or refinement, one-by-one. When the review is finished, the artist and epigraphers iron out any questions at the wall. When everyone is in agreement, the artist adds the corrections to the inked drawing back in the studio using the collation sheets as a guide, the transferred corrections are checked for accuracy by the epigraphers, and the drawing receives a final review by the field director back at the wall itself. During the course of the collation process, the first epigrapher is also responsible for translations and preliminary analysis of the texts being documented, which are later compiled and synthesized by the senior epigrapher.

Jennifer Kimpton collating at Medinet Habu

Recording Color

Ancient Egyptian inscribed wall reliefs were usually intended to be plastered with whitewash and painted with bright mineral-based pigments. Sadly, most painted details are now missing from the ancient Egyptian monuments, scoured away by time and the elements. But not all monuments are lacking paint. Because many more details were painted than carved, traces of painted details often survive within carved outlines. The convention for paint boundaries in the Chicago House black-and-white line drawings is a row of small consecutive dots. The eye sees the dots as a thin gray line, differentiated from the carved lines that are rendered with unbroken ink lines. In some rare and wonderful cases when the painted surface is well preserved, full-color reproduction is necessary. Today, color photography, both film and digital, can be utilized to capture and reproduce true color and is now standard in documentation and publication. At the time the Epigraphic Survey and Saqqara Expedition started work, color photography was not adequate for the task of color reproduction. Instead, a number of talented epigraphic artists mixed colors at the wall and, instead of penciling photographs, painted directly on the photographic enlargements, matching the colors by eye as they saw them. Printed in Austria and Germany, the published results are sensational and form an exciting component of the early published record of both expeditions. Chief among the extraordinary artists who perfected this technique were Alfred Bollacher and Virgilio Canziani, whose work can be seen throughout the Epigraphic Survey Medinet Habu volumes. Saqqara Expedition field director Prentice Duell himself was responsible for many of the color paintings in the Mereruka volumes.

Krisztián Vértes drawing in color at Medinet Habu

Recording Invisible Surfaces- While photography and the Chicago House photographic drawing method are very well suited for certain types of inscribed wall surfaces, they are not perfect for all situations. Each inscribed area has its own set of conditions and challenges, and the Chicago House epigraphic team uses whatever methodology is appropriate to record it. Wall areas that are partly obscured behind later walls or are behind columns cannot be photographed, for instance. In such cases, tracing (using paper or transparent tracing film) is the only way to document them, and those tracings can be reduced digitally and integrated with the photographs and/or drawings. Reused blocks in floors, foundations, and walls where inscribed surfaces are barely visible present another situation in which photography is impossible. The reused material in the walls and floors of Khonsu temple, Karnak, which the Epigraphic Survey is currently documenting, is a perfect example. In many instances this material cannot even be traced and can barely even be seen in the spaces between the floor-blocks. But with care, aluminum foil can be slipped in the gaps between the blocks, and rubbings made of the invisible surfaces (utilizing long sticks with cotton tips), with extraordinary results. These rubbings can then be traced, reduced digitally, and used to make scale drawings, which are then inked according to our normal weighted line conventions. The possibilities are endless; the present author has used the aluminum foil technique quite successfully in ancient Memphis to record blocks that were actually underwater!

The Graffiti Project- Facsimile drawings of graffiti throughout the Medinet Habu complex are now also made digitally, utilizing a modified form of the Chicago House method. Scanned or digital photographs are the basis for digital tracing using Photoshop and Illustrator software on drawing tablets. Preliminary drawings are done in the studio as a layer over the digital photograph, which is then printed and taken to the wall or roof area for collation. Corrections are added back in the studio and checked again at the wall or roof area. It is quite possible that a time will come when large-format negative film and photographic paper are no longer available, and all our drawings will have to be done digitally. We will be ready! We are also looking forward to experimenting with three-dimensional imaging as a future methodology in our Luxor program. Whatever the method of recording, be it drawing on photographs, tracing with paper or transparent film, doing aluminum foil rubbings, or digital drawings, consultations between the artist, epigraphers, and field director (the consensus of all talents combined) ensure a scientific facsimile drawing that is faithful to every detail preserved on the wall. This is the new definition of what is generally referred to as the Chicago House method. Our goal is to continue improving, refining, and broadening it.

Christina di Cerbo modifying digital tracings

Christina di Cerbo recording graffiti at Medinet Habu

Once the facsimile drawing has received its final review and is cleared for publication by the director, it is archived at Chicago House until the whole monument being recorded is finished, after which all drawings are taken back as a group to Chicago where the publications are organized and printed. The hard-copy drawings are scanned in high resolution for plate production (after which they are permanently archived at the Oriental Institute), the digital drawings are integrated, and the whole publication is designed electronically. All of the Epigraphic Survey’s publications are now printed digitally, allowing accessibility in electronic as well as in hard copy. And now, in an exciting new program inaugurated by the Oriental Institute, all past Epigraphic Survey publications have been scanned as well and are available without charge in PDF format for free electronic download from the Oriental Institute Publications website.

Additional reading material about the Oriental Institute and the Epigraphic Survey:

To reach the Oriental Institute on the web

To read the Oriental Institute Annual Reports

To read about the Epigraphic Survey’s work

To read the annual Chicago House Bulletins

To download the Epigraphic Survey Publications for free in PDF format

0 comment(s)

Leave a comment(We'll keep your email address private)