Recording Djehutihotep. Digital epigraphy in a Middle Kingdom governor’s tomb at Dayr al-Barsha (Part 1)

Written by Marleen De Meyer, KU Leuven, Department of Archaeology, Postdoctoral researcher & Assistant Director for Egyptology and Archaeology, Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo

When reproducing an ancient art, let us by all means be accurate,

and employ every kind of mechanical aid to obtain that objective;

but let that mechanical aid be our assistant, not our master.

Howard Carter [1]

Fig. 1: The north hill of Dayr al-Barsha with the tomb of Djehutihotep on the far left (Photo M. De Meyer)

Starting in 2017 a team of KU Leuven (Belgium) has initiated a new epigraphic recording of the Middle Kingdom tomb of Djehutihotep at Dayr al-Barsha in Middle Egypt. Djehutihotep was a provincial governor of the 15th Upper Egyptian Nome, in office during the reigns of Senwosret II–III. His rock-cut tomb chapel high on the north hill contains some of the finest Middle Kingdom decoration in paint and relief which has, however, suffered fairly severe damage by later quarrying activity, earthquakes, and vandalism (figs 1–3).

Fig. 2: The tomb of Djehutihotep (Photo M. De Meyer)

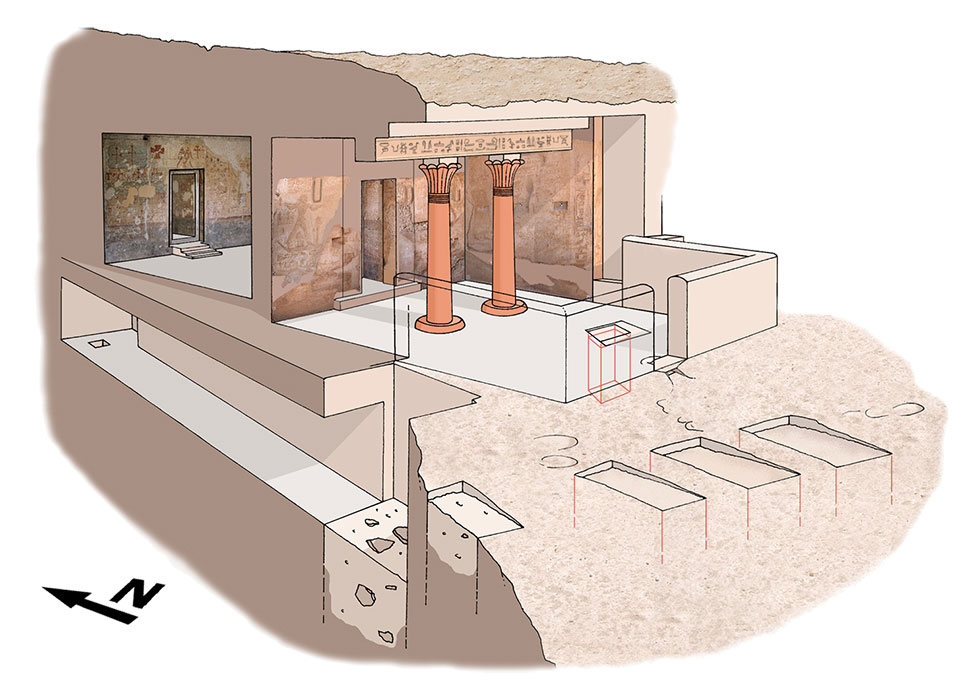

Fig. 3: Reconstruction drawing of the tomb of Djehutihotep (Drawing M. Hense)

Its exquisite decoration, and the presence of the unusual scene in which a colossal alabaster statue of the governor is transported on a sledge, attracted the attention of early epigraphers. In the winter of 1891–1892 a team of the Egypt Exploration Fund made a first recording under the direction of Percy Newberry. His draughtsmen were a young 17-year old Howard Carter and Marcus Blackden, and their 1894 publication still remains the standard reference work for this tomb. [2] However, while the work of Newberry’s team is praiseworthy for the quality achieved in a minimal amount of time, it contains many errors and lacunae, and the large overview drawings do not do justice to the fine details and subtle use of colour in the tomb. [3]

Following the theft of a relief fragment that was hacked out of the interior chapel in May 2015, the urgency of a new and detailed copy of this tomb became evident. Funding was obtained from KU Leuven [4] in order not only to record the present state of the tomb, but also to digitally reconstruct its original appearance as much as possible by integrating the many decorated wall fragments that are preserved both at the site and at several museums worldwide into a virtual model.

As with any epigraphic project, deciding on a method and workflow was a crucial first step. That this method should be digital, and not by tracing on transparent plastic, was self-evident, but the choice between a vector-based or a raster-based program was not. Since our original preference went to a vector drawing, one scene was drawn in Adobe Illustrator as a case study.

Case study of a scene on the west wall of Djehutihotep’s inner chapel [5]

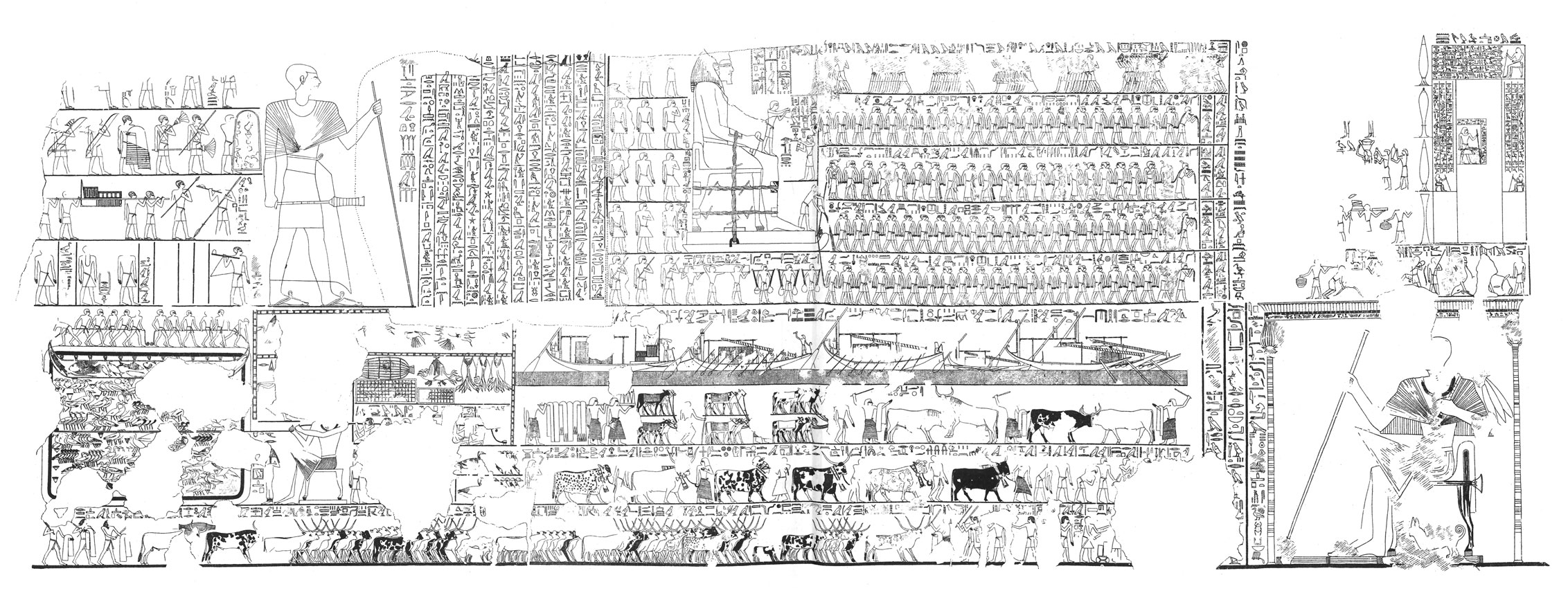

While the scene of the dragging of the colossal statue of the governor is the best-known scene of the entire tomb, it is usually looked at in isolation. However, this scene forms part of a larger narrative covering the entire upper part of the western interior wall of the tomb (figs 4–5). To its left, the statue is being followed by a large figure of Djehutihotep himself accompanied by his relatives, guards, and high officials. To the right the gate of the building (now destroyed) is shown towards which the statue was transported, in front of which a number of offering bearers are depicted. The latter was only summarily rendered in Newberry’s 1894 publication, perhaps because the walls were still covered with dirt (figs 6–7).

Fig. 4: The west wall of the rock-cut chapel of Djehutihotep (Photo M. De Meyer)

Fig. 5: Newberry’s rendering of the west wall of the tomb of Djehutihotep (Newberry, Percy E. El Bersheh I: The Tomb of Tehuti-Hetep; ASE 3, London: Egypt Exploration Fund, [1894], pl. XII)

Fig. 6: The offering bearers in front of the gate of Djehutihotep’s ka-chapel (Photo M. De Meyer)

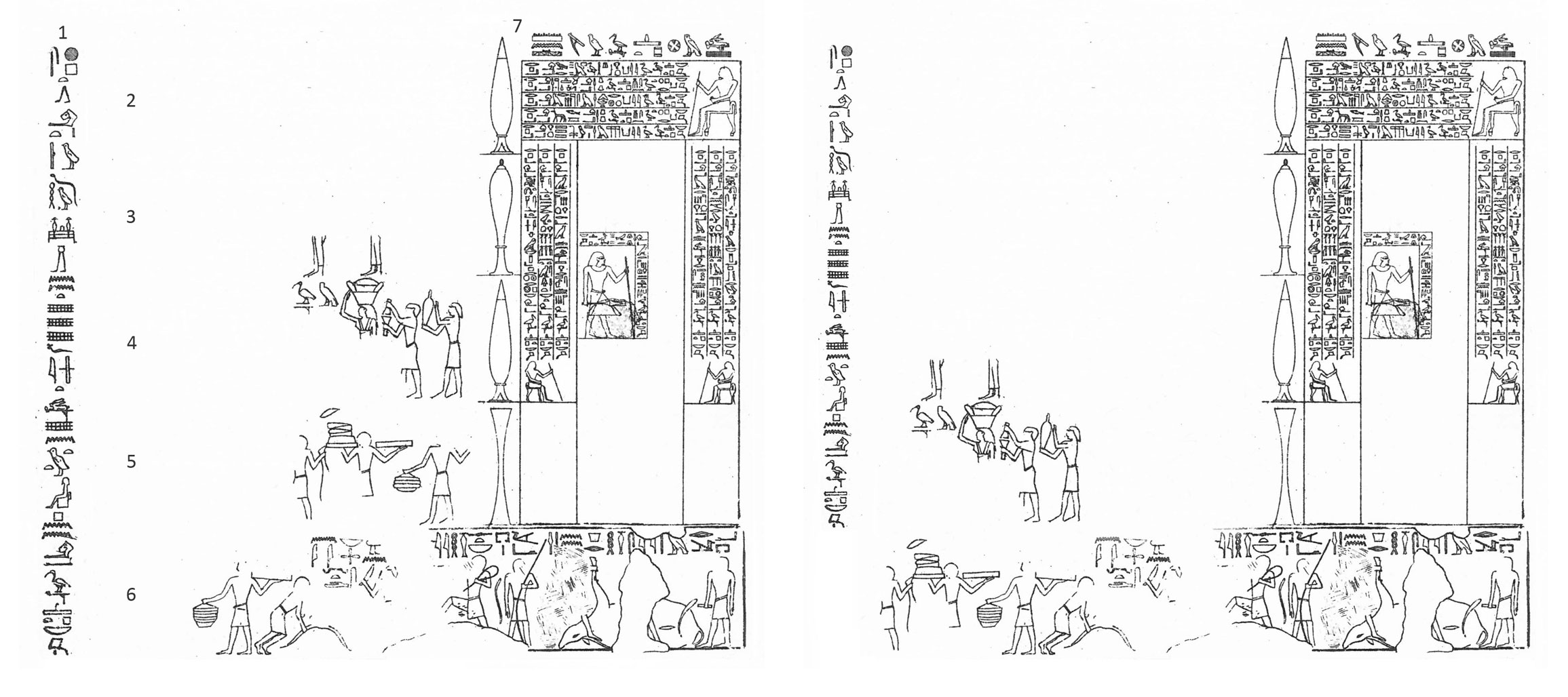

Fig. 7 (left): Newberry’s drawing of the offering bearers in front of the ka-chapel of Djehutihotep (Newberry, Percy E. El Bersheh I: The Tomb of Tehuti-Hetep; ASE 3, London: Egypt Exploration Fund, [1894], pl. XII). The line numbers are added by the author. Fig. 8 (right): Corrected version of Newberry’s drawing (M. De Meyer)

Today, however, much more of this scene is visible (fig. 6). A new copy makes it clear that Newberry’s drawing is not only incomplete, but also incorrect. When reassembling the loose sheets of drawings of this wall for final inking in the UK, something must have gone wrong, and several offering bearers ended up in the wrong registers. The man carrying a large joint of meat (rib cage) in his right hand at the end of register 5, is in fact the same man who is depicted first in register 6, and both he and the two men in front of him should have been placed in register 6. The figures that Newberry rendered in registers 3 and 4, actually belong in registers 4 and 5. A corrected drawing of Newberry is rendered in fig. 8. Such mistakes are not obvious to the reader when no photographs are published alongside the drawings, as is the case with the Newberry publication, but this example amply demonstrates the caution with which such old publications should be approached.

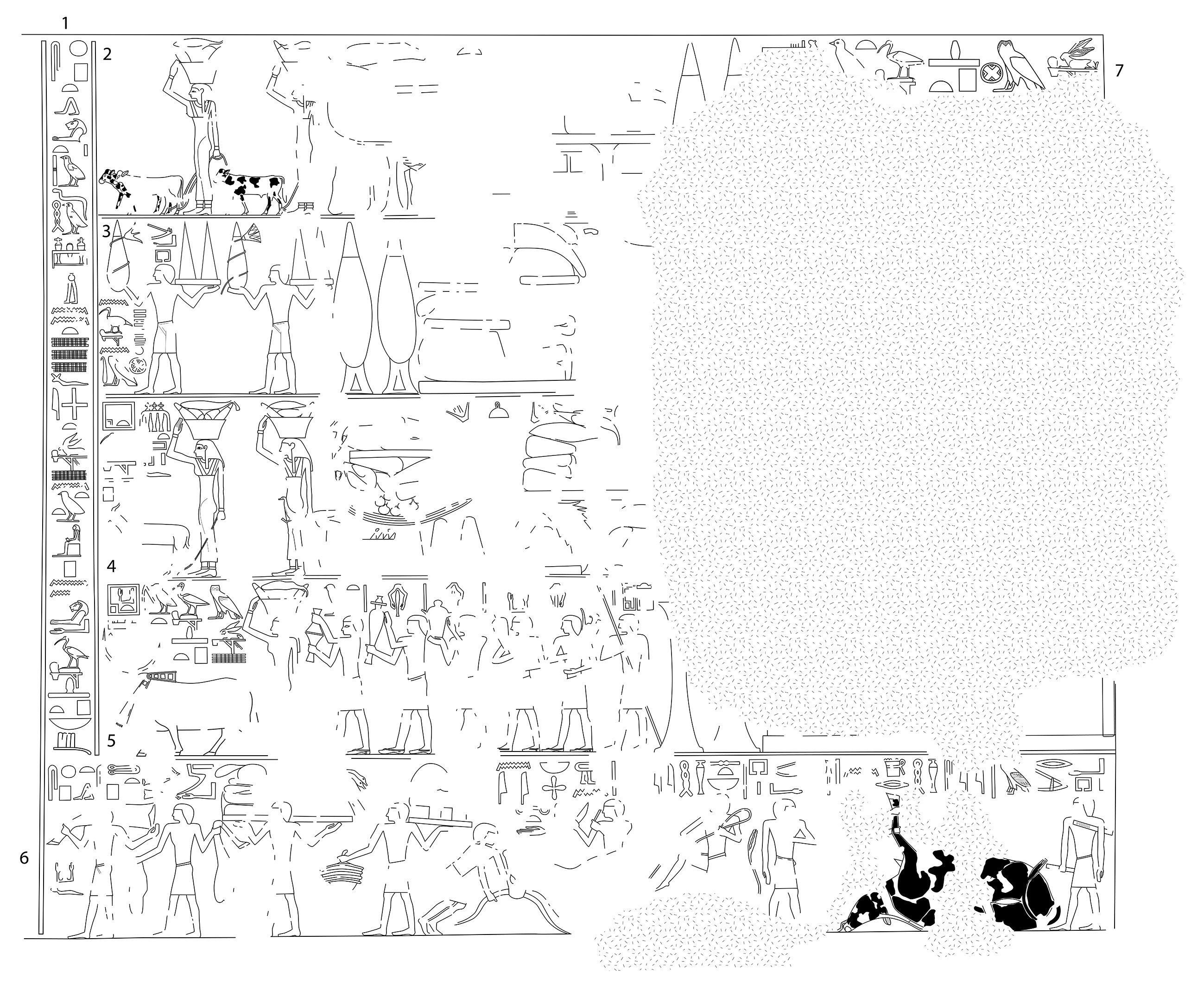

Fig. 9: New preliminary drawing in Adobe Illustrator of the offering bearers in front of the ka-chapel of Djehutihotep

This entire scene was traced anew in Adobe Illustrator, and fig. 9 shows the result. Most of the offering bearers and all of the inscriptions accompanying them were never published by Newberry, but this scene turns out to divulge important information about the supply chain of the ka-chapel of Djehutihotep.[6] While the vector-based drawing is a clean and clear drawing, it is perhaps too clean for the wall that it is supposed to represent. Often only spots of paint are preserved without a clear outline associated with them, and these kinds of traces are notoriously difficult to record in Adobe Illustrator. Moreover, rendering the damage in a realistic way is also hard to do in Illustator, and the patterned fill that was chosen in this case does not convey anything about the type of damage on the wall.

During the process of making the vector drawing, it became clear that a raster-based drawing would allow for a more natural, one might even call it artisanal style of copying a painting or relief that was in itself also not the result of a mathematically correct line, but the work of a talented free-hand artist. The “grace of line” in Egyptian art, as T.G.H. James [7] so aptly phrased it when he described what mattered most to Howard Carter as a draughtsman, is done better justice with a recording method that gives the epigraphist a kind of freedom that is not found in mathematical vectors. If Howard Carter were alive today, I like to think that he would also choose Photoshop over Illustrator, as indicated by this entry in his notebook [8] : “I could never understand the axiom: “Mechanical exactitude of facsimile copying is required rather than freehand or purely artistic work”…but why purely artistic work should necessarily be inaccurate I fail to fathom.”

Fig. 10: Digital epigraphy in the tomb of Djehutihotep

The method employed nowadays in the tomb of Djehutihotep by our team of KU Leuven will be elaborated upon in Part 2 by Toon Sykora.

Further reading

De Meyer, Marleen and Harco Willems. “The Regional Supply Chain of Djehutihotep's Ka-Chapel in Tjerty.” In G. Andreu-Lanoë and F. Morfoisse(eds), Sésostris III et la fin du Moyen Empire. Actes du colloque des 12-13 décembre 2014 Louvre-Lens et Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, Cahiers de recherches de l’Institut de papyrologie et d'égyptologie de Lille 31, Lille: Université de Lille, 2016–2017, 33–56.

De Meyer, Marleen and Kylie Cortebeeck (eds). Djehoetihotep. 100 jaar opgravingen in Egypte / Djehoutihotep. 100 ans de fouilles en Égypte. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 2015.

Newberry, Percy E. El Bersheh I: The Tomb of Tehuti-Hetep; ASE 3, London: Egypt Exploration Fund, [1894]

[1] James, T.G.H. “Howard Carter's Epigraphic Creed.” In Sesto congresso internazionale di egittologia: Atti, Turin: Tipografia Torinese, 1992, 341.

[2] Newberry, Percy E. El Bersheh I: The Tomb of Tehuti-Hetep; ASE 3, London: Egypt Exploration Fund, [1894]. For Carter’s early experiences as an epigraphist, see James, T.G.H. "The Very Best Artist.” In E. Goring and C.N. Reeves (eds), Chief of Seers. Egyptian Studies in Memory of Cyril Aldred, London: Kegan Paul, 1997, 164–174.

[3] A few select scenes were copied as watercolours in order to convey exactly this, but most of them were never published. They can now be browsed through on the website of the Griffith Institute.

[4] This research features within the 'Puzzling Tombs' project (3H170337) funded by the KU Leuven Bijzonder Onderzoeksfonds (C1 Project). All images are copyright of the Dayr al-Barsha Project.

[5] This scene is studied in detail in De Meyer, Marleen and Harco Willems. “The Regional Supply Chain of Djehutihotep's Ka-Chapel in Tjerty.” In G. Andreu-Lanoë and F. Morfoisse(eds), Sésostris III et la fin du Moyen Empire. Actes du colloque des 12-13 décembre 2014 Louvre-Lens et Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, Cahiers de recherches de l’Institut de papyrologie et d'égyptologie de Lille 31, Lille: Université de Lille, 2016–2017, 33–56.

[6] For detailed information about the contents of this scene, see the reference in n. 5.

[7] James, T.G.H. “Howard Carter's Epigraphic Creed.” In Sesto congresso internazionale di egittologia: Atti, Turin: Tipografia Torinese, 1992, 339.

[8] Carter Notebook 15 at the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, p. 68ff. See also James, Thomas Garnet Henry. “Howard Carter's Epigraphic Creed.” In Sesto congresso internazionale di egittologia: Atti, 339–344. Turin: Tipografia Torinese, 1992. p. 340.

0 comment(s)

Leave a comment(We'll keep your email address private)